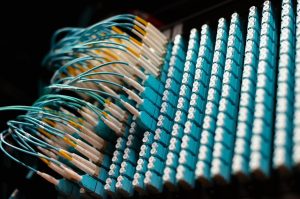

The strategic deployment and expansion of the fiber network in Africa represents the most critical infrastructure project for the continent’s digital and economic future, fundamentally transforming connectivity from Cape Town to Cairo. In particular, this high-capacity backbone is not just about faster internet; it’s a catalyst for innovation, education, and economic inclusion on an unprecedented scale. Consequently, understanding its current state, trajectory, and hurdles is essential for investors, policymakers, and anyone invested in Africa’s growth. Moreover, while undersea cables form the continent’s digital lifelines to the world, a complex and rapidly evolving web of terrestrial and metro fiber is now bringing that capacity directly to businesses and homes.

The Current State of Fiber Optic Infrastructure Across Africa

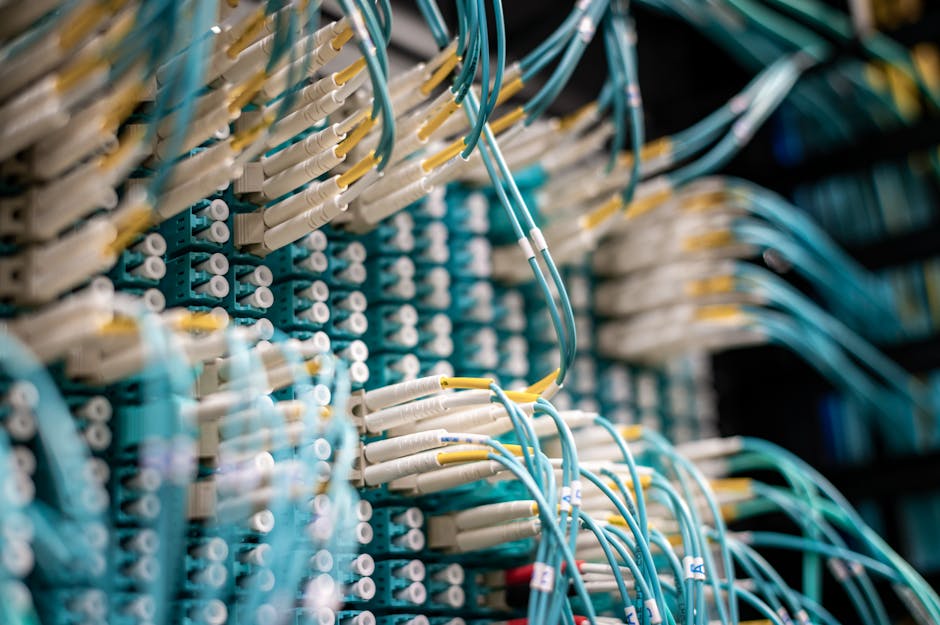

Today, Africa’s fiber landscape is a patchwork of advanced and emerging networks, with significant disparities between coastal nations and landlocked regions. For instance, countries like South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, and Egypt have established relatively mature national fiber backbones, often operated by a mix of incumbent telcos, private players, and government initiatives. Meanwhile, the Eastern African region has seen remarkable progress, largely driven by the success of companies like Liquid Intelligent Technologies and the widespread adoption of mobile money, which demands robust underlying connectivity. However, the central and western interior still faces considerable gaps, where reliance on expensive satellite or microwave links persists, creating a digital divide that mirrors physical geography.

Furthermore, the total terrestrial fiber route length in Africa has seen a compound annual growth rate exceeding 20% over the last decade, yet it remains a fraction of the density found in Europe or North America. A key metric is fiber-to-the-tower (FTTT) penetration, which is crucial for enabling 4G and 5G mobile services. In addition, many national networks are not fully interconnected, leading to situations where data traffic between neighboring countries may still route through Europe, increasing latency and cost. This fragmentation is a primary focus for regional economic communities and infrastructure investors aiming to create a seamless digital market.

Undersea Cables: Africa’s Digital Lifelines to the Global Internet

Africa’s connectivity to the global internet is almost entirely dependent on a growing constellation of submarine cable systems landing on its coasts. Historically, the continent suffered from a lack of diversity, but the last 15 years have witnessed an explosion of new cables. Major systems like SEACOM, EASSy, WACS, and ACE were joined by a new generation, including the Google-backed Equiano, the Facebook-led 2Africa project—which will be the longest submarine cable in the world—and the Djoliba cable. Each new cable landing brings terabits of additional capacity, driving down international bandwidth prices and improving reliability through redundant paths.

However, the benefits are not evenly distributed. Most cables land in a handful of hubs: South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, Djibouti, and Morocco. Consequently, landlocked nations remain vulnerable to the political and infrastructural stability of their coastal neighbors for access. Moreover, the “last mile” challenge applies to the “last kilometer” from the beach landing station to the national backbone, where bottlenecks can still occur. The development of open-access cable landing stations, as seen in Nigeria with the WACS cable, is a positive trend that allows multiple service providers to leverage the international capacity competitively.

“The 2Africa cable, once completed, will connect 33 countries across Africa, Europe, and Asia, effectively encircling the continent and potentially doubling its total international capacity. This represents a paradigm shift from scarcity to planned abundance,” notes a regional infrastructure analyst.

Key Drivers Fueling the Expansion of Fiber in Africa

Several powerful economic and technological forces are converging to accelerate fiber rollout across the continent. Firstly, the insatiable demand for data, driven by smartphone adoption, video streaming, and cloud services, makes wireless networks alone unsustainable without a fiber backbone. Mobile network operators are the largest customers for wholesale fiber capacity, as they seek to offload traffic and prepare for 5G. Secondly, government digital transformation agendas and “smart city” projects in capitals like Kigali, Nairobi, and Lagos create direct demand for municipal fiber networks to connect government offices, schools, and hospitals.

Thirdly, the financial sector’s digitalization, including mobile money platforms like M-Pesa, requires ultra-reliable, low-latency connections between data centers and agent networks. Furthermore, the gradual migration of enterprise IT systems to the cloud mandates direct, secure fiber links to cloud on-ramps and internet exchanges. Finally, supportive policy and regulatory reforms in several countries, which encourage infrastructure sharing and reduce right-of-way fees, are lowering the capital expenditure barriers for network builders.

The Role of Mobile Network Operators (MNOs)

MNOs are both primary consumers and increasingly builders of fiber assets. Companies like MTN, Airtel, and Vodacom have launched significant fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) and enterprise-focused initiatives, recognizing that owning infrastructure provides a competitive edge in service quality and cost. Their extensive tower portfolios also serve as natural aggregation points for fiber networks, creating a dense mesh of potential connectivity.

Major Challenges and Barriers to Ubiquitous Fiber Deployment

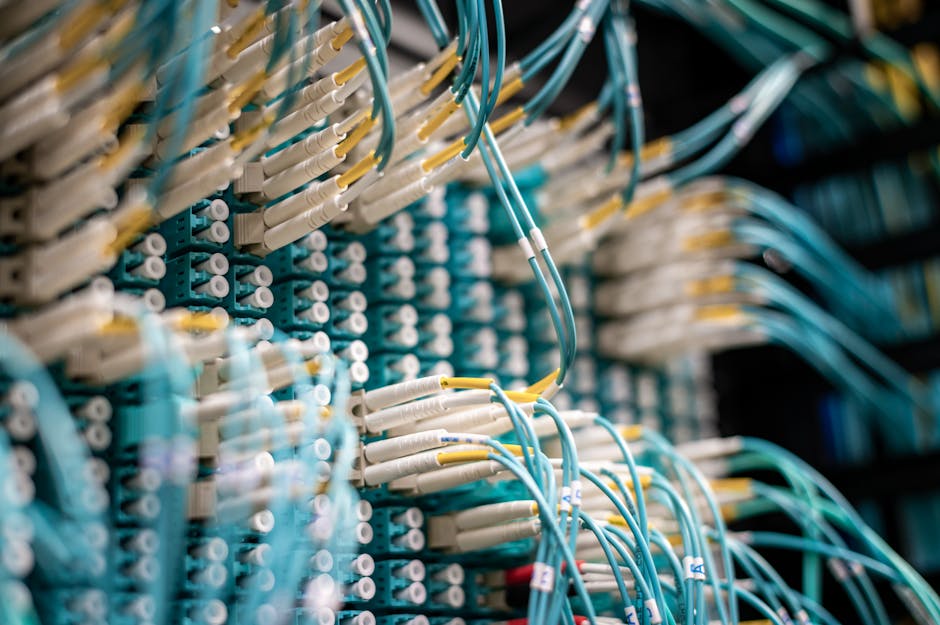

Despite the progress, formidable obstacles continue to impede the pace and reach of fiber deployment. The most pervasive challenge is the high cost of civil works, which can constitute up to 70% of a terrestrial fiber project’s budget. Trenching through urban areas is expensive and logistically complex, while laying fiber across vast, uninhabited regions presents its own set of difficulties. Vandalism and theft of fiber cable, often mistaken for copper, cause frequent service outages and financial losses for operators.

Regulatory hurdles and bureaucratic delays in obtaining wayleaves (permits to dig) from numerous local and national authorities can stall projects for months or years. In some markets, a lack of effective infrastructure sharing mandates leads to wasteful duplication of fiber routes along the same corridors. Moreover, the commercial viability of extending fiber into rural and low-income areas remains questionable without creative public-private partnership models or universal service fund subsidies. The question remains: how can operators justify the investment in regions with low population density and limited ability to pay?

The Critical Role of Terrestrial Cross-Border Fiber Links

While undersea cables connect Africa to the world, terrestrial cross-border links are the arteries that integrate the continent internally. These links are essential for creating a regional digital economy, reducing latency for intra-African communication, and lowering the cost of internet access by keeping traffic local. Projects like the Central African Backbone (CAB) and the East African Submarine System (EASSy)’s terrestrial extensions are vital in this regard. Furthermore, they enhance resilience; if one country’s link to an undersea cable is cut, traffic can be rerouted through a neighboring nation’s network.

The development of these links is often spearheaded by regional blocs like the East African Community (EAC) or the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). However, geopolitical tensions, differing regulatory regimes, and security concerns in border areas can complicate implementation. Successful cross-border projects typically involve consortiums of operators and governments sharing the cost and ownership, aligning incentives for maintenance and expansion. The One Africa Network initiative aims to harmonize policies to make cross-border data flow as seamless as cross-border voice calls have become.

Metro Fiber and the Last-Mile Connectivity Challenge

Bringing high-speed internet from the national backbone to the end user—the infamous “last mile”—is where the battle for digital inclusion is truly fought. Metro fiber networks within cities are expanding rapidly, connecting business districts, universities, and high-density residential areas. Operators like Dark Fibre Africa in South Africa and Internet Solutions have built extensive urban rings. The business model often involves leasing “dark fiber” (unlit, unmanaged fiber strands) to internet service providers, mobile operators, and large enterprises, who then light it with their own equipment.

For last-mile access, Fiber-to-the-Home (FTTH) is growing in affluent suburbs and gated communities, while Fiber-to-the-Building (FTTB) is common in commercial high-rises. However, the economics of serving informal settlements or low-cost housing areas with direct fiber are challenging. Consequently, alternative solutions are being deployed, such as using fiber to feed high-capacity wireless point-to-multipoint systems or Wi-Fi hotspots, effectively creating a hybrid network. The key is to get fiber as close as possible to the community, then use the most cost-effective technology for the final connection.

Innovative Deployment Techniques

To reduce costs, companies are adopting innovative techniques like micro-trenching (cutting very narrow, shallow trenches), using existing sewer or drainage ducts, and aerial deployment on utility poles. In some cases, governments are mandating the inclusion of empty fiber conduits (“ducts”) in all new road construction and real estate developments, a practice known as “dig once.”

Investment Landscape: Who is Funding Africa’s Fiber Build-Out?

The capital required to blanket a continent in fiber is immense, attracting a diverse array of investors. Traditional telecom operators remain major investors, often through their capital expenditure budgets. However, independent tower companies like IHS Towers are expanding into fiber, leveraging their site portfolios. Furthermore, specialized fiber companies like Liquid Intelligent Technologies, CSquared, and WIOCC have attracted significant private equity and developmental finance. For instance, Google’s investment in the Equiano cable and its subsequent funding for terrestrial fiber extensions in countries like Togo and South Africa highlight the interest of global tech giants.

Development finance institutions (DFIs) such as the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC), the African Development Bank (AfDB), and the European Investment Bank (EIB) play a crucial role by providing patient debt and equity for projects that have strong developmental impact but may be perceived as too risky by purely commercial investors. Public-private partnerships (PPPs) are also gaining traction, where a government provides rights-of-way and guarantees, and a private consortium finances, builds, and operates the network. The influx of investment is a strong vote of confidence in Africa’s digital future.

The Future Outlook: 5G, IoT, and Smart Cities

The future applications of digital technology in Africa will be entirely dependent on the pervasive reach and robustness of its fiber optic backbone. The rollout of 5G mobile networks is not possible without a dense fiber network to connect the multitude of small cells required for high-frequency spectrum. Similarly, the Internet of Things (IoT) for agriculture, logistics, and utilities will generate vast amounts of data that need to be backhauled efficiently. Smart city visions for traffic management, public safety, and energy distribution rely on thousands of sensors connected via fiber or fiber-fed wireless networks.

Looking ahead, we can expect continued consolidation in the fiber operator market, as scale becomes increasingly important. The convergence of fiber, data center, and cloud services into integrated offerings will be a key trend. Moreover, as networks become more software-defined, the ability to dynamically allocate bandwidth and create virtual private networks will make fiber assets even more valuable. The ultimate goal is a continent where high-speed, affordable connectivity is a utility as accessible and reliable as electricity, unlocking the full innovative potential of Africa’s population.

Conclusion: A Connected Continent Within Reach

The journey to comprehensively connect Africa with fiber is well underway, marked by both extraordinary achievements and persistent challenges. From the deep-sea beds hosting cutting-edge submarine cables to the trenches being dug along rural roads, this infrastructure is the foundation of the Fourth Industrial Revolution on the continent. While the path forward requires continued investment, smarter regulation, and innovative business models, the momentum is undeniable. The expansion of the fiber network in Africa is more than a technical project; it is a central pillar in the story of Africa’s economic transformation, educational advancement, and global integration in the 21st century.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Which African country has the best fiber network?

South Africa currently has the most extensive and mature fiber network, with widespread FTTH and FTTB coverage in major cities and a well-developed national backbone. Kenya and Nigeria are also leaders, with aggressive rollout plans and high levels of investment in both terrestrial and metro fiber.

How does fiber internet in Africa compare in cost to other regions?

While international bandwidth prices have plummeted due to new submarine cables, the end-user cost for fiber internet in Africa is still generally higher than in Europe or Asia, especially for high-speed plans. However, prices are falling rapidly in competitive urban markets, and the value proposition is improving significantly.

What is the biggest threat to fiber network growth in Africa?

The single biggest threat is infrastructure vandalism and theft, which causes service disruptions and imposes heavy repair costs on operators. Other major threats include regulatory instability, currency volatility affecting equipment imports, and the high cost of capital for long-term infrastructure projects.

How important are data centers to the fiber ecosystem?

Extremely important. Data centers are the natural endpoints and traffic hubs for fiber networks. The growth of carrier-neutral data centers in cities like Johannesburg, Nairobi, Lagos, and Accra is both a driver and a result of fiber expansion, creating localized content and cloud access points that improve performance for end-users.