The deployment and expansion of the fiber network in Africa represents one of the most critical infrastructure stories of the 21st century, fundamentally reshaping the continent’s digital and economic landscape. For years, Africa’s connectivity was defined by expensive satellite links and limited, congested submarine cables, creating a significant digital divide. However, the past two decades have witnessed a seismic shift, with an unprecedented surge in terrestrial and submarine fiber optic investments. This digital backbone is now the primary engine for mobile broadband, cloud services, enterprise connectivity, and the promise of a truly inclusive digital economy. Consequently, understanding the state of Africa’s fiber optic infrastructure is key to comprehending its future trajectory in the global digital arena. This comprehensive guide delves into the history, current landscape, formidable challenges, key players, and the immense opportunities that lie ahead for this transformative network.

The Historical Evolution of Fiber in Africa

The journey of high-speed connectivity in Africa began not on land, but under the sea. For most of the late 20th century, international communications were dependent on a few, often government-controlled, satellite gateways and the initial generation of submarine cables like SAT-2, which offered limited capacity. The turning point arrived in the early 2000s with the landing of the SEACOM cable system in 2009, which was privately financed and offered a new model for infrastructure development. This event marked the beginning of the end of the satellite monopoly and sparked a wave of competitive cable investments along Africa’s eastern and western coasts. Meanwhile, terrestrial fiber builds were initially slow, often led by incumbent national telecom operators (PTTs) and focused on connecting major cities, leaving vast rural areas in a connectivity desert.

Furthermore, the liberalization of telecom markets across the continent created a fertile ground for competitive infrastructure providers. Companies like Liquid Intelligent Technologies (formerly Liquid Telecom) embarked on ambitious cross-border terrestrial builds, creating pan-African fiber highways. The entry of hyperscalers—tech giants like Google, Meta (Facebook), and Amazon—has further accelerated the pace in recent years. Their demand for massive, low-latency capacity to serve a booming user base has led to privately funded, state-of-the-art submarine cable projects like Google’s Equiano and Meta’s 2Africa, the latter being the most extensive subsea cable system ever built. This evolution from scarcity and monopoly to abundance and competition forms the bedrock of today’s fiber network in Africa.

The Current Landscape: Submarine and Terrestrial Backbones

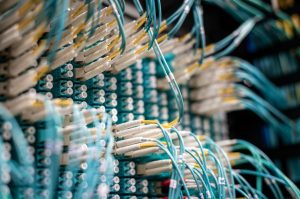

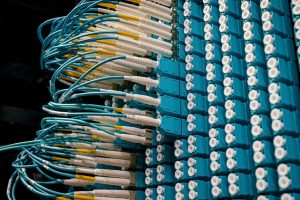

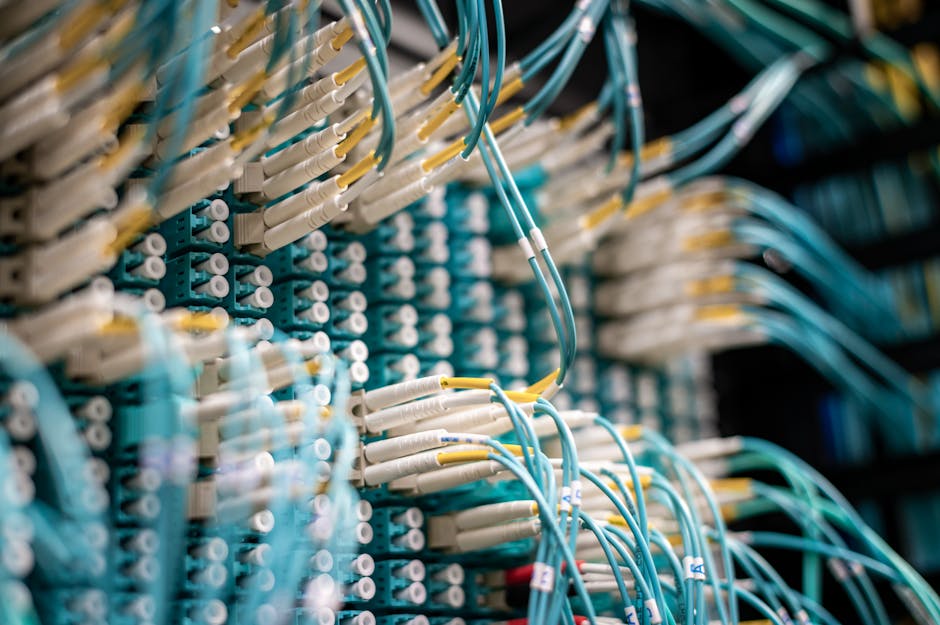

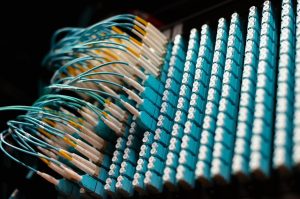

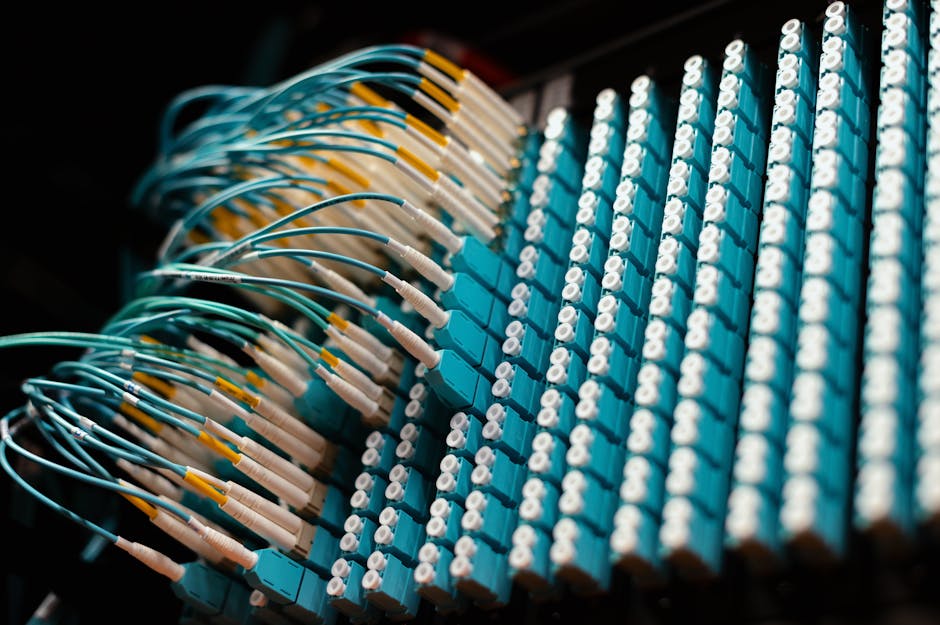

Today, Africa’s fiber optic ecosystem is a complex, interconnected web of submarine cables encircling the continent and terrestrial networks stitching nations together inland. The submarine cable map is now densely populated, with over a dozen major systems landing at more than 40 coastal points from South Africa to Egypt and Senegal to Somalia. Key systems include the West Africa Cable System (WACS), Africa Coast to Europe (ACE), and the newer, higher-capacity cables like 2Africa, Equiano, and the Djibouti Africa Regional Express (DARE). These subsea arteries carry over 99% of international data traffic, providing the vital bandwidth lifeline to the global internet.

The Terrestrial Challenge and Success Stories

On land, the picture is more varied but increasingly robust. Major regional corridors have been established, such as the Eastern Africa Submarine Cable System (EASSy) terrestrial extension and the Central African Backbone (CAB) project. South Africa, Kenya, Nigeria, and Egypt boast the most developed national fiber networks, with extensive reach to secondary cities and some rural areas. Pan-African operators like Liquid Intelligent Technologies have built a network spanning over 100,000 kilometers, connecting countries from South Africa to Kenya and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Similarly, the Africa Data Centres’ ecosystem relies on extensive fiber rings around major business districts in cities like Johannesburg, Nairobi, and Lagos to provide resilient connectivity to enterprises.

However, the “last-mile” challenge—connecting the fiber backbone to individual homes, businesses, and cell towers—remains a significant hurdle. While Fiber-to-the-Home (FTTH) is growing in affluent urban suburbs, and Fiber-to-the-Tower (FTTT) is critical for 4G/5G mobile backhaul, the cost of deployment and right-of-way issues often slow progress. Consequently, the current landscape is a tale of two realities: thriving, hyper-connected digital hubs in major cities, and underserved regions where the fiber backbone passes nearby but does not directly connect the end-user, a phenomenon often called the “middle-mile gap.”

Key Players Driving Fiber Network Expansion

The expansion of Africa’s digital backbone is driven by a diverse coalition of stakeholders, each with distinct motivations and strategies. Traditionally, incumbent national operators like Telkom South Africa, Safaricom in Kenya, and Orange Group across Francophone Africa were the primary builders, often leveraging their existing rights-of-way along railway and road networks. Today, they are joined by aggressive, specialized infrastructure companies. Liquid Intelligent Technologies stands out as a pioneer, having built one of the largest independent fiber networks. Additionally, companies like CSquared, initially a Google-backed venture, focus on building open-access metropolitan fiber networks in cities like Kampala, Accra, and Monrovia, allowing multiple internet service providers (ISPs) to compete on a shared physical infrastructure.

Moreover, the hyperscale content providers have become perhaps the most influential new players. Google’s Equiano cable, landing in South Africa, Namibia, Nigeria, and St. Helena, is designed with advanced space-division multiplexing technology for immense capacity. Similarly, Meta’s 2Africa cable will connect 33 countries across Africa, Europe, and the Middle East. These players are not just investing in cables; they are also investing in terrestrial infrastructure to ensure their data can efficiently reach inland points of presence and data centers. Finally, government-led initiatives and public-private partnerships (PPPs), such as the Central African Backbone project funded by the World Bank, play a crucial role in connecting landlocked nations and regions deemed less commercially attractive by private capital alone.

Major Challenges and Barriers to Ubiquitous Access

Despite remarkable progress, the path to a truly ubiquitous and affordable fiber network in Africa is fraught with persistent and complex challenges. The most immediate barrier is the high capital expenditure (CapEx) required for trenching, laying duct, and installing fiber, especially in remote or geographically difficult terrain. This financial hurdle is compounded by often lengthy and bureaucratic processes for obtaining right-of-way permits from national, regional, and local authorities. In many countries, multiple agencies must grant approval, leading to delays that can stretch projects by years and inflate costs significantly. Vandalism and theft of fiber cable, often for the scrap value of the inner sheath, also cause frequent service outages and costly repairs.

Regulatory and Policy Hurdles

On the regulatory front, inconsistent policies and a lack of harmonization between neighboring countries create major impediments for cross-border networks. Issues include restrictive licensing regimes, difficulties in obtaining spectrum for wireless last-mile links, and protectionist policies that favor state-owned incumbents. Furthermore, the high cost of international bandwidth, though falling, is still inflated in many countries due to a lack of competitive landing stations or monopolistic practices. A critical question remains: how can regulators balance the need for infrastructure investment with the imperative to ensure affordable access for consumers? Another significant barrier is the lack of reliable and affordable electricity in many areas, which is essential for powering the repeaters and amplifiers needed on long-haul fiber lines and for running network equipment at cell sites and data centers.

The Economic and Social Impact of Fiber Connectivity

The transformative power of a robust fiber network in Africa extends far beyond faster internet speeds; it is a catalyst for broad-based economic growth and social development. At a macroeconomic level, the World Bank estimates that a 10% increase in broadband penetration can lead to a 1.38% increase in GDP growth for low- and middle-income countries. Fiber underpins the digital economy, enabling e-commerce platforms like Jumia and Takealot, fostering fintech innovation such as mobile money (M-Pesa), and allowing African tech startups to compete globally by leveraging cloud computing services hosted in local data centers. For enterprises, reliable fiber connectivity reduces operational costs, enables seamless communication with global partners, and facilitates the adoption of advanced technologies like Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) and Customer Relationship Management (CRM) systems.

Socially, the impact is equally profound. In education, fiber backbones enable digital learning platforms, provide students in remote areas access to global knowledge repositories, and support video-based distance learning. In healthcare, they facilitate telemedicine, allowing specialists in urban centers to consult with patients and doctors in rural clinics, and enable the rapid transmission of large medical imaging files. Furthermore, improved connectivity promotes financial inclusion by supporting mobile banking and digital payment systems, and enhances government service delivery through e-governance initiatives. Essentially, fiber optic infrastructure is not just a utility but a foundational platform for achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) across the continent.

Technological Innovations Shaping the Future

The future of Africa’s fiber network will be shaped by a convergence of cutting-edge technological innovations that promise to increase capacity, reduce costs, and extend reach. In the submarine domain, new cables like 2Africa and Equiano are deploying the latest optical fiber technology, such as space-division multiplexing (SDM), which uses multiple fiber pairs within a single cable to exponentially increase potential capacity into the petabit-per-second range. This ensures these systems will not become bottlenecks for decades to come. On the terrestrial front, advancements in fiber technology itself, like G.652.D and G.654.E fibers, offer lower attenuation and support higher-power signals, enabling longer spans between amplification points—a critical advantage for crossing Africa’s vast, sparsely populated regions.

Moreover, innovations in deployment techniques are reducing costs and disruption. Micro-trenching involves cutting a very narrow, shallow trench, which is faster and cheaper than traditional methods, ideal for urban last-mile deployments. Fiber-in-duct solutions allow new fiber to be blown through existing, unused underground ducts. For crossing rivers, mountains, or protected areas, air-blown fiber and high-altitude balloon or drone-based deployment are being explored. Furthermore, the integration of fiber with wireless technologies is crucial. Fiber forms the essential backhaul for 4G and 5G mobile networks, and new wireless solutions like microwave E-band and millimeter-wave (mmWave) radios are being used for high-capacity, short-hop connections where fiber deployment is temporarily impossible or too expensive, creating hybrid network architectures.

The Critical Role of Data Centers and Internet Exchange Points (IXPs)

A high-capacity fiber network is only as valuable as the infrastructure it interconnects. This is where data centers and Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) become the vital organs of the digital ecosystem. Data centers provide the secure, powered, and cooled facilities where content, cloud services, and enterprise applications are hosted. The growth of carrier-neutral data centers like those operated by Africa Data Centres, Rack Centre, and Teraco in South Africa allows multiple network operators to colocate their equipment, creating dense interconnection hubs. When content from global platforms like Google, Netflix, or Microsoft is cached locally in these data centers, it dramatically reduces latency for African users and keeps local internet traffic within the country or region, lowering the cost of international transit.

IXPs are equally critical. They are physical locations where multiple ISPs, mobile network operators, and content providers connect their networks to exchange traffic directly, rather than routing it through expensive international hubs in Europe or North America. A thriving local IXP, such as the Nigerian Internet Exchange Point (IXPN) or the Kenya Internet Exchange Point (KIXP), keeps domestic traffic local, improving speeds and reducing costs for everyone. For instance, before the establishment of robust IXPs, an email sent from a user in Lagos to a recipient in Abuja might have traveled to London and back, adding significant delay and cost. The synergy between fiber, data centers, and IXPs creates a powerful “flywheel effect”: more local content attracts more networks to interconnect, which lowers costs and improves performance, which in turn attracts more investment in fiber and data centers, creating a virtuous cycle of digital growth.

Future Outlook and Strategic Recommendations

The future outlook for Africa’s fiber network is one of cautious optimism, characterized by continued expansion, deeper penetration, and smarter integration. The next decade will likely see the completion of major pan-African terrestrial corridors, finally connecting all capital cities and major economic zones with high-capacity fiber. Submarine cable capacity will become abundant with the full operation of 2Africa and other new systems, driving international bandwidth prices down further. The focus will increasingly shift to the “middle and last mile”—building out from the backbone to reach secondary cities, towns, and ultimately, homes and businesses. This will involve innovative financing models, such as infrastructure sharing and open-access networks, to make these less densely populated routes commercially viable.

Strategic recommendations for accelerating this future are clear. Governments must prioritize creating enabling regulatory environments by streamlining right-of-way processes, implementing fair and transparent licensing, and promoting infrastructure sharing to reduce duplication of effort. Public-private partnerships should be leveraged to fund connectivity in underserved areas where purely commercial models fail. Policymakers should also actively support the growth of local IXPs and data center ecosystems through incentives and supportive legislation. For private investors and operators, the opportunity lies in leveraging new technologies to lower deployment costs and in developing innovative business models, such as wholesale-only open-access networks, that can profitably serve a wider customer base. Ultimately, the goal must be to transform the fiber network in Africa from a series of connected lines on a map into a pervasive, affordable, and resilient utility that empowers every citizen and enterprise on the continent.

“The investment in Africa’s fiber optic backbone is not merely an infrastructure project; it is the single most important enabler for education, healthcare, innovation, and economic participation in the digital age. Closing the connectivity gap is synonymous with closing the opportunity gap.” – An industry analyst specializing in African telecommunications.

In conclusion, the evolution of the fiber network in Africa is a narrative of transformative progress against significant odds. From its beginnings with a few submarine cables to today’s complex web of terrestrial and subsea infrastructure, fiber has become the central nervous system of the continent’s digital awakening. While challenges like high costs, regulatory hurdles, and last-mile access persist, the momentum is undeniable. Driven by a mix of private investment, hyperscale demand, and public-sector initiatives, the network is expanding in both capacity and reach. The synergistic growth of supporting infrastructure like data centers and IXPs multiplies its impact. Looking ahead, the continued strategic expansion of this fiber foundation will determine the pace at which Africa can harness the full potential of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, ensuring that its growing population is not just connected, but empowered to innovate and thrive on the global stage.